Here is an article that was published today in the canadian newspaper National Post. It describes certain aspects of our research. Allison Hanes was a pleasure to work with and was easy to talk to and i think she did a really great job explaining our research. She got this little detail wrong however, the information from the tongue usually goes to the somatosensory cortex in sighted controls, not the motor cortex. I sent them this video of one of my subjects (Mr. L., some of you may recognize him from Decouverte on Radio-Canada; see: http://www.radio-canada.ca/actualite/v2/decouverte/niveau2_8722.shtml). Take a look at this video on the National Post website, this very short clip shows Mr. L negociating his way through the obstacle course where we tested subjects this summer:

http://video.canada.com/VideoContent.aspx?&fl=&popup=1

send me your comments on my blog!

I hope to hear from you soon,

Daniel

'Sight' that tingles

Canadian researchers part of team testing revolutionary technology for the blind: Nationalpost.com

Allison Hanes, National PostPublished: Tuesday, February 06, 2007

Last summer Mike Ciarciello went to a Montreal laboratory, donned a pair of goggles mounted with a camera and stuck a strange device the size of a quarter in his mouth.

By constantly moving his head from side to side to scan the room and pressing his tongue against a square of 100 tiny electrodes, the 36-year-old, who has been blind since birth, was able to "see" for the first time.

For a few short hours, Mr. Ciarciello stepped out of his arm's-length universe of shadows and light to make out a black triangle projected on to a white wall, navigate an obstacle course, even perceive that a person was walking in front of him.

"The guy came in on my left then moved to my right. I was actually able to see that. I was like, 'Hey get out of my way!' "he said with a laugh.

It was an indescribable experience for the teacher and musician who normally feels his way through life with his hands and a cane.

The blind could be able to see with their tongues within a decade due to the latest advances in technology and neuropsychology.

An electrical-impulse-emitting device being developed by researchers in Canada, Denmark and the United States is already allowing those like Mr. Ciarciello to detect movement and sense objects at a distance. One day it may allow them to perceive faces and colours -- even read text.

Maurice Ptito, a Universite de Montreal neuropsychologist testing the revolutionary technology on people like Mr. Ciarciello, hopes the invention will do for the blind what the hearing aid did for the deaf.

"For blind people it's so important, because it means they could do it without a dog or a cane," he said in an interview from Copenhagen, where he is on a year-long sabbatical. "They could feel motion, things coming to them, or things moving from left to right. It's quite fantastic actually."

The devices, called tongue display units, do not bestow the gift of sight. What they can do is help the blind experience the world around them in a much more profound way than has previously been possible.

"You are not going to recover vision, but we can substitute something else for it," he said. "If you don't have eyes, you can't see ... But what's nice is that they can feel the world through their tongues, and they can feel it at a distance. For them, it's something that is really incredible."

In laboratories in Montreal and Copenhagen, test subjects born without sight have been making remarkable progress in sensing their way. Tiny cameras perched on eyeglasses or helmets translate images into tingling sensations, not unlike morse code.

Prof. Ptito describes the feeling as comparable to champagne bubbles.

The tongue can be trained to glean information from the electrical impulses it transmits to the brain, distinguishing the difference between a triangle and a square for example, or even the letter T.

Because the tongue is a wet milieu -- and one of the most sensitive organs in the human body --it is the perfect conduit.

Subjects are being tested to perceive black geometric shapes on a white background. Black is indicated by a tingling of maximum intensity while white is conveyed by no sensation at all.They have also been taught a handful of letters from the alphabet allowing them to spell out short words.

Those testing the tongue units have not yet ventured beyond the confines of a lab, but Prof. Ptito said they will soon begin trials outdoors.

It was an indescribable experience for the teacher and musician who normally feels his way through life with his hands and a cane.

The blind could be able to see with their tongues within a decade due to the latest advances in technology and neuropsychology.

An electrical-impulse-emitting device being developed by researchers in Canada, Denmark and the United States is already allowing those like Mr. Ciarciello to detect movement and sense objects at a distance. One day it may allow them to perceive faces and colours -- even read text.

Maurice Ptito, a Universite de Montreal neuropsychologist testing the revolutionary technology on people like Mr. Ciarciello, hopes the invention will do for the blind what the hearing aid did for the deaf.

"For blind people it's so important, because it means they could do it without a dog or a cane," he said in an interview from Copenhagen, where he is on a year-long sabbatical. "They could feel motion, things coming to them, or things moving from left to right. It's quite fantastic actually."

The devices, called tongue display units, do not bestow the gift of sight. What they can do is help the blind experience the world around them in a much more profound way than has previously been possible.

"You are not going to recover vision, but we can substitute something else for it," he said. "If you don't have eyes, you can't see ... But what's nice is that they can feel the world through their tongues, and they can feel it at a distance. For them, it's something that is really incredible."

In laboratories in Montreal and Copenhagen, test subjects born without sight have been making remarkable progress in sensing their way. Tiny cameras perched on eyeglasses or helmets translate images into tingling sensations, not unlike morse code.

Prof. Ptito describes the feeling as comparable to champagne bubbles.

The tongue can be trained to glean information from the electrical impulses it transmits to the brain, distinguishing the difference between a triangle and a square for example, or even the letter T.

Because the tongue is a wet milieu -- and one of the most sensitive organs in the human body --it is the perfect conduit.

Subjects are being tested to perceive black geometric shapes on a white background. Black is indicated by a tingling of maximum intensity while white is conveyed by no sensation at all.They have also been taught a handful of letters from the alphabet allowing them to spell out short words.

Those testing the tongue units have not yet ventured beyond the confines of a lab, but Prof. Ptito said they will soon begin trials outdoors.

The technology is the brainchild of U.S. doctor and scientist Paul Bach-y-Rita, a pioneer in a field called substitution theory, who believed people actually see with their brains, not their eyes.

Daniel-Robert Chebat, the Ph D student who conducted tests on 36 blind subjects in the Montreal lab, said one of the most exciting findings is that the electrical impulses transmitted by the tongue to the brain activate the visual cortex: "We know that this type of information normally should go to the motor cortex and yet it's in the visual cortex ... The question is, are we unmasking old connections that are already there or are we rather creating new ones in the brain?"

Using the technology patented by Dr. Bach-y-Rita's Wisconsin- based company requires considerable training before the test subjects can make sense of all the tiny pops and buzzes on the tongue.

For starters, blind people are commonly taught to stay as still and straight as possible when they use a cane or a guide dog to get around.

"What I tell them is the opposite," Mr. Chebat explained. "Since the subject is wearing this camera on his forehead, as he moves this image changes. He learns to recognize that, as with eyesight ... when we move our eyes or we move our heads, the images changes."

It is often the first time these test subjects learn how to process information on shifting perspective and distance: "One of the obstacles we had was a bar blocking the entire width of the hallway ... And so if you couldn't judge distances very well, there's no way you could have stepped over it," Mr. Chebat said. "I say, 'Look at your feet. Do you see your feet? They're on the tip of your tongue if look down, if you're wearing black shoes. Then if you look up, do you see that bar? Now how long did it take you to make that movement? OK, so how far do you think that bar is from you?' So through trial and error, they learn to judge the distances and how the head movements translate to distances."

After relying his whole life on his hands and fingers to navigate the world, Mr. Ciarciello said using the technology took some getting used to.

The biggest challenge, he said, was rewiring his reactions to make use of new information being supplied to his brain.

"I realized: 'Don't wait until you bump into an object to go around it -- go around it before you bump in to it!' "he said. "When you're not used to seeing things from a distance, it's a whole new ball game."

Blind people's worlds are essentially limited to what is at arm's-length. They take in information -- the placement of objects, the shape of people's faces, writing in braille -- using their hands, or a white cane. The tongue devices have the power to change all that -- expanding their surroundings from the car parked a block away to the mountain on the horizon.

"It's hard to describe to people who take it for granted that they can see," Mr. Ciarciello said. "This opens up a whole other door."

Visit our homepage to watch an exclusive video showing how this technology is helping the blind to "see."

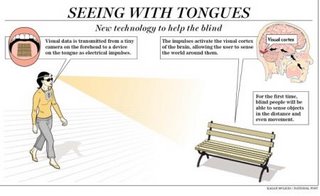

SEEING WITH TONGUES: New technology to help the blind...Visual data is transmitted from a tiny camera on the forehead to a device on the tongue as electrical impulses. The impulses activate the visual cortex of the brain, allowing the user to sense the world around them. For the first time, blind people will be able to sense objects in the distance and even movement. Photograph by : Kagan McLeod, National Post